You are NOT your disorder.

The human mind loves labels.

As we receive information, we associate it with that which we already know, enabling processes like inference-making, judgement, and memorization. For example, even if you have never tasted a French macaron, you can infer that it is a sweet dessert because at the grocery store, it sits next to the chocolate fudge cupcakes and snickerdoodle cookies. If you find a macaron at Whole Foods, you might make the judgement that it is healthy because, well, you found it at Whole Foods. And you will certainly remember that you found it at this specific health food store because of its enormous price tag. Such inferences, judgements, and memories both incite and reinforce your mind’s decision to label the macaron, “healthy.”

The conclusions we make based on labels are not necessarily true; surely eating an entire box of sugary macarons from Whole Foods’ bakery can’t be considered “healthy.” But when the mind wants a conclusion to be true, it will make every possible justification to turn correlation into causation and temporal possibility into permanent fact. We rationalize our macaron binge with its “healthy” label that we constructed earlier; we reassure ourselves that it was probably full of organic ingredients and that the beautiful, fit woman in yoga leggings behind us at the checkout counter also had a box in her cart (note how we so often turn to other people to rationalize our actions, rather than turning inward and considering what is really right for us). We thus use the macaron’s “healthiness” to hide our wrong actions and intentions from ourselves, limiting our ability to reveal and eradicate the underlying insecurities that made us binge in the first place.

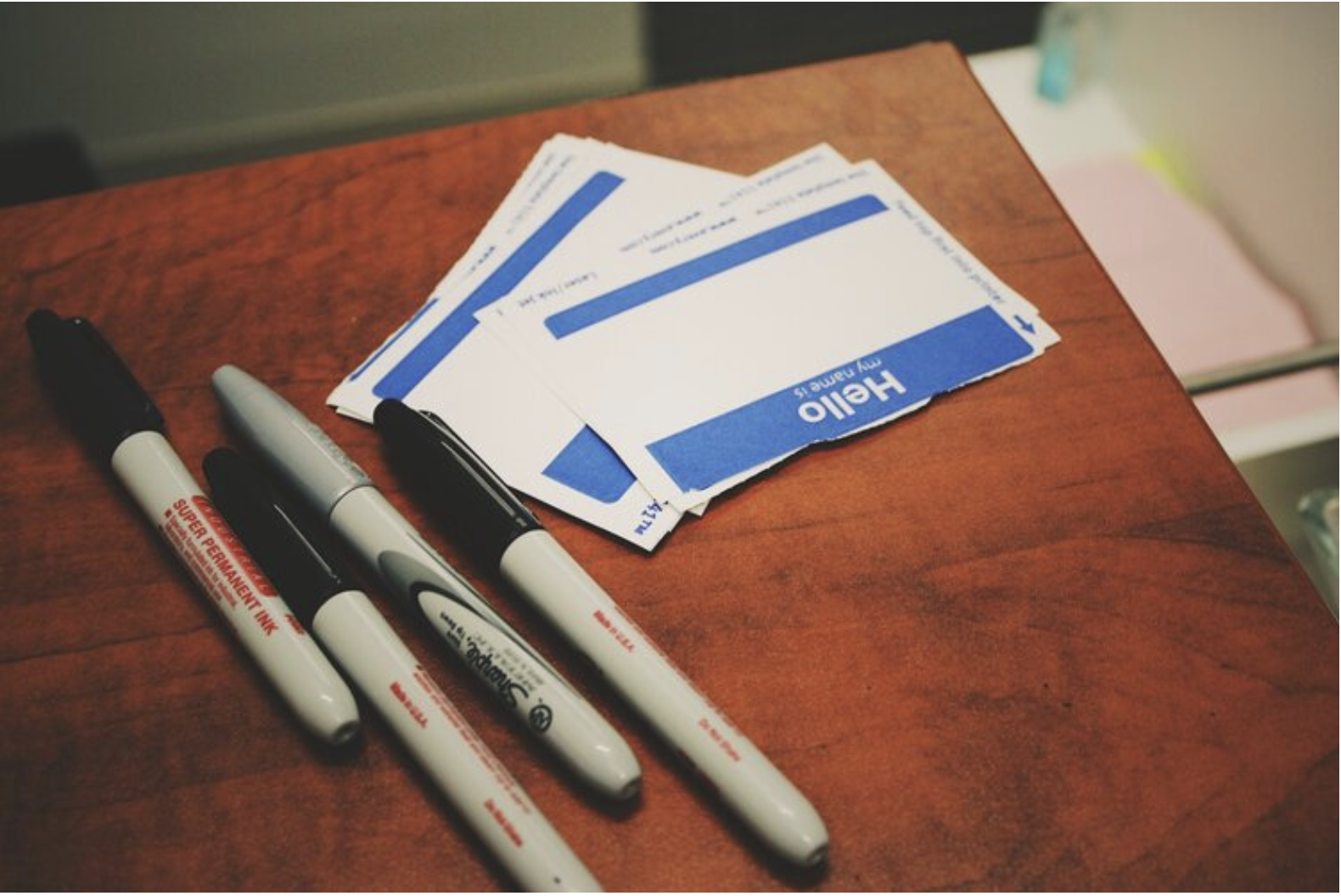

Sticky notes like this, when placed in your journal, on your mirror or bedside table, or anywhere that you frequent, is the perfect reminder to honestly portray yourself, to yourself.

The danger of labels is that because human psychology is so complex and beautiful, we have the power to literally speak our beliefs into existence.

For example, if you tell all your friends that the macaron is an ancient French superfood (which, spoiler alert, it is not), and they tell all their friends, and you all start throwing macaron parties because of their supposed magical health qualities, then you have conditioned the world around you to believe something that simply isn’t true. Soon enough, everyone is inferring that macarons will make you live longer and remembering them alongside kale and kombucha.

Likewise, if you infer from past experiences that you have Binge Eating Disorder, and if you tell all your friends that you have Binge Eating Disorder, and if your counselor tells you that you have Binge Eating Disorder, then you can bet your bottom dollar that you and everyone else will act exactly as if you have Binge Eating Disorder. This is part and parcel of the Law of Attraction. At this point, most people start identifying with the disorder. In typical Alcoholics Anonymous fashion, we declare to ourselves and the world, “Hi, my name is ____, and I am a binge eater,” or “Hi, my name is ____, and I am an anorexic.” The thing about these labels is that they are harder to scrape off than the gooey residue from that sun-baked bumper sticker that has been on your car for five years. The longer they sit, the harder they are to remove.

What labels do you want to assign to yourself?

To clarify, I am not denying the reality of anyone’s personal battles or conditions (but if you were quick to the defense, do take a moment to ask yourself why). What I mean is that there is a difference between saying you are “an anorexic” and saying that you “have anorexic tendencies or habits.” Bottom line: you are not your disorder.

So what happens if we do assign these labels to ourselves?

Just like with the macaron fallacy, we will infer, judge, and remember our lives with questionable levels of accuracy. Someone who has a history of binging might infer that they should never be left alone with food again, judge themselves as weak, and remember their life’s history only in terms of when they were binging and when they were not. And here’s the kicker: after using these inferences, judgements, and memories to construct their identity as “a binge eater,” they will subsequently use that identity to rationalize their actions, avoid accountability, and, ultimately, avoid growth and healing. I know because this was once me.

And maybe eating a box of macarons isn’t all that bad. Maybe you just wanted to treat yourself one day. Or maybe you got carried away because, guess what? Macarons are delicious, and you are human! The problem only arises when you deny what really made you go for that fourth, fifth, sixth macaron in one sitting and when you attempt to rationalize your binge by lying to yourself about being a victim of some official-sounding disorder that is out of your control. Because you are not a victim. You have, and always will have, complete control over how you relate to food. Sometimes we just don’t want to admit it because doing so concedes the need to exert effort and self-control. But while it might be easier to be a victim, it is far less fulfilling than being the hero of your own story. A victim, through self-deceit, is unable to stop themselves from repeating mistakes. A hero, through honesty, learns from their mistakes, prevents them from happening again, and thus nurtures their own integrity and well-being.

The silver lining in all of this is that if we can speak negative labels into existence, we can also speak positive labels into existence.

A macaron and gelato I recently enjoyed in none other than Paris itself!

Instead of saying, “I have depression,” try saying, “I am a source of light, and I am becoming a happier and better person every day.” Instead of saying, “I have Binge Eating Disorder,” try saying, “I forgive myself for the past, and I am healing my relationship with food. I am more grateful than ever for the sustenance on my plate.” Make these phrases and labels your mantras; write them in your journal every morning, put them on sticky notes and post them around your room, make them your phone’s background, repeat them to yourself in meditation -- do whatever it takes to audibly and visibly reinforce your positive affirmations.

It is important to acknowledge your struggles. But it is equally important to acknowledge your opportunities for growth and to honor your natural propensity to pursue them. Rather than labeling yourself as a victim of life’s challenges, label yourself as a hero who is overcoming them.

Eat as many macarons as you want. The act itself is neither good nor bad. It is how you reflect upon it, and the labels you use in doing so, that really matters.